2002 Mongolian Expedition

A Wild Ride Through Western Mongolia

Follow-On Discoveries from the 1999 Expedition...

Mongolia is about as far as one can get from a home in the United States. For much of the year, when it's noon in New York, it's midnight in Mongolia. In other words, they are on opposite sides of the Earth. But Mongolia is also a Mecca for paleontologists because of the great wealth of fossils that have been discovered there, ever since Roy Chapman Andrews and his crew from the American Museum of Natural History's Central Asiatic Expeditions discovered dinosaur eggs there in the 1920's.

In August of 2002, Art Ballard and Lowell Dingus of the InfoQuest Foundation joined Luis Chiappe from the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County on a trip to the westernmost reaches of Mongolia near the Kazakhstan border to prospect for fossils of dinosaurs and flying reptiles. Like most such reconnaissance trips, things didn't go exactly as planned. It turned out to be a much more challenging trip than we anticipated, as you will discover in the following account developed from our field notes. Lowell's notes appear in standard type, while Art's are italicized--Lowell

Lowell Dingus and the Lost Treasure of Genghis Khan

This story really has nothing to do with the fabled lost treasure tomb of Genghis Khan, whose burial site has never been found; this is the true narrative of a paleontology reconnaissance trip in the Gobi Desert of Mongolia. I gave my narrative this lurid title to get your attention, and because it annoys my friend, Dr. Dingus.

In February of 2002 I had the good fortune to accompany Drs. Lowell Dingus of Infoquest and Luis Chiappe of the Los Angeles County Museum to Patagonia while they worked to further refine the stratigraphy and extent of their fabulous dinosaur nest and egg discovery, chronicled in National Geographic magazine and other media. (see my trip journal on this website, “Search for the Lost Valley of Auca Mahuida”).

While sitting around the campfire the Patagonian wilderness, I listened with envy to Lowell and Luis’ tales of Mongolian dinosaur adventures. So much envy in fact that I shamelessly let drop that I might accept an invitation go with them on their planned Mongolian reconnaissance trip to the far northwest Gobi Desert in August of that year... Art

August 2-4 Having participated in several earlier expeditions to the Gobi Desert in southern Mongolia, we knew we would need to spend several days in the capital, Ulaanbaatar, in order to get organized. Lowell got there first and met with our host, Batdelger, from the National Museum of Natural History in Mongolia. Most Mongolians only use one name, although on formal documents they use the name of their mother as a family name. Although Batdelger was an ornithologist rather than a paleontologist, he was excited to have the chance to find some dinosaur fossils, as well as to continue his survey of birds in the western part of his country, especially the census for his favorite bird, the Saker falcon.

Originally our plan was to drive from Ulaanbaatar several hundred miles west to the city of Hovd. However, Batdelger informed us that such a drive might not be possible due to outbreaks of hoof-and-mouth disease, as well as marmot plague, in some of the regions along the way. These animal-based diseases had triggered quarantines for which roads were closed to prevent spreading the diseases. As Lowell and Batdelger waited for Luis and Art to arrive, Batdelger kept in touch with the health authorities in the various provinces and began to make plans to fly to Hovd instead of drive... Lowell

August 5 Batdelger and Lowell went to the airport to meet Luis. The easiest way to get from the US to Mongolia is to first fly to Beijing, a very long flight of about 20 hours. Then, after recuperating and adjusting to the time change for a day or two, the flight from Beijing to Ulaanbaatar takes only about 90 minutes…at least that's the way it's supposed to work. Occasionally, however, bad weather makes it impossible to land in Ulaanbaatar, and on this day a small sandstorm blossomed in the late afternoon. As a result, the flight that Luis was on had to land across the Russian border in Irkutsk on the shore of Lake Baykal and wait a couple of hours before continuing on to Ulaanbaatar. But eventually, the sandstorm dispersed, and the plane was able to land about 9 pm.

After Luis checked into our hotel, we discussed the present state of our plans. Unfortunately, there were not enough empty seats on the plane for all four of us to fly on the same day to Hovd, so three of us would fly on the 9th and one on the 10th... Lowell

August 6 The long days of organizational meetings began in earnest. We still wanted to try and arrange for all of us to fly together to Hovd, which would require that we check daily at the offices of the Mongolian airline, MIAT. After an hour of negotiations, we were able to get two tickets for the 9th and two for the 10th, so that Lowell could fly with Art after he arrived on the 9th. Luis and Batdelger would leave on the 9th to begin making arrangements with the provincial officials in Hovd.

We also had to get permits to collect fossils in the regions around Hovd from the Mongolian Academy of Sciences. One of our paleontological colleagues, Dr. Barsbold, was especially helpful in this regard, working to secure the permits as well as getting us copies of the best geologic maps for the area.

In addition, our agreement for work with Batdelger stipulated that we would consult with Mongolia's National Museum of Natural History to try and help them improve their exhibits. So, Luis and Lowell spent several hours meeting with the director and toured the museum with several staff members to see their exhibits.

Meanwhile, Art arrived in Beijing... Lowell

August 7 We spoke with Art by phone in the morning to see if he could fly from Beijing earlier than the 9th in case we could all get tickets to fly to Hovd on that day. He agreed to try.

Then Luis, Batdelger and Lowell met with senior staff members at the American Embassy to inform them of our plans and our meetings with the staff of the Natural History Museum. The main source of funding for our trip had been arranged through a US government grant promoting scientific and cultural exchanges between our two countries.

In the afternoon, we met with Barsbold to pick up copies of the geologic maps. We also were finally able to arrange for four tickets to fly to Hovd on the 9th, which made it imperative that Art make it to Ulaanbaatar by the 8th. We tried to call Art at his hotel, but the front desk said he had checked out. We thought that maybe he had gone to the train station, but unbeknownst to us, Art was on his way to the Beijing airport. When we returned to our hotel, his colleague in Beijing called to say that he would arrive later in the day. Before going to the airport to meet him, we did some shopping to buy a tent for Batdelger and some camp chairs... Lowell

August 8 Our last day in Ulaanbaatar before leaving was filled with shopping and packing. We still needed some camping supplies and plaster in case we needed to make jackets around fossils. We also tried to register our passports with the police, but we couldn't locate the right office. We changed a good deal of money at the bank so that we would have plenty for the road. Finally, we gave a box of chocolate to the people at the airline office who had helped us rearrange our tickets. By the end of the day, we were exhausted, but exhilarated at the prospect of actually leaving for the field in the morning... Lowell

August 5 From Houston, Texas, I fly to Dallas; connect with a flight to Los Angeles, then with a flight to Tokyo, where I continue to Beijing then on to Ulaanbaatar after a few days rest in Beijing. I am worried about my luggage with so many connections. It would not be pleasant to begin an expedition without my tent, sleeping bag, and favorite field corkscrew. I am so pleased to be on my way to Mongolia, I can hardly contain myself. I am wearing my desert boots and safari jacket on the business class flight, and wonder what the business travelers must think. They ignore me. I wish someone would ask where I’m going. I have a couple of martinis and consider just elbowing my quiet Japanese neighbor and say “howdy partner, how ya doin’? I’m on my way to look for dinosaurs in the Gobi Desert!” But I restrain myself.

I love geology. No matter where you are on this planet, there is something geological to look at and think about. Geology is so broad a discipline, no matter what your particular interest is, there is something for you; biology, chemistry, physics, mathematics, even literature and philosophy. Paleontology is a branch of geology, and I think what attracted me to it so strongly was time-traveling; the feeling of actually seeing the events of millions of years ago while looking at the evidence of them at your feet. Fossil bone, fossil sea shells, footprints, current ripples in the sediment, even tiny ancient rain-drop craters in the sand all tell stories to the geologist.. Anyway, I’m now on a trip to Mongolia, to look at Cretaceous strata in the Gobi Desert over 80 million years old, and I’m pinching myself, I can’t believe I am on this great adventure... Art

August 7 I arrive in Beijing pretty tired, about midnight. What a surprise Beijing is. The airport is spotless, one of the best airports I have ever seen. The mural of the Great Wall stretches hundreds of meters, really gorgeous. The Chinese officials are friendly, helpful. My luggage made it! I get a taxi to the hotel, ready to sleep. I wake up early, around 0530 A.M, I try to call Lowell at the Tuuvshin Hotel in Ulaanbaatar, can’t get through.

I had planned to have a couple of days in Beijing to visit the Great Wall and other sites, but I get a message from Lowell at my hotel that I should come ASAP to Ulaanbaatar, there is trouble with our plans to travel to the Western Gobi from there. Something about hoof and mouth and bubonic plague epidemics. Bloody hell! Bubonic plague? For heaven’s sake! My company has an office in Beijing, and the manager is a friend. He arranges a driver for me, and his secretary helps me get a flight. I had considered taking the train to Ulaanbaatar, but my friend’s secretary tells me it is much too dangerous. I intend to take the train anyway... Art

8 August Got the flight to Ulaanbaatar early in the morning, glad to miss the train ride, really. I wasn’t sure whether or not Lowell and Luis would meet me at the airport, but was confident I could make my way to their hotel. Flying into Ulaanbaatar I could see it was a small city with no very tall buildings, which had grown up on the banks of a meandering river. I caught sight of my first gers (called yurts by the Russians;ger rhymes with hair) on the outskirts of the city; some were right in the town, behind houses and inside fences. The city reminded me of the town of Anaco, in East Venezuela, which is also located in a wide plain flanked by rolling hills. No river or gers at Anaco, though.

I was pleasantly surprised to find Luis and Lowell to greet me at the airport. They were with a very special Mongolian scientist, an ornithologist named Batdelger, Champion of the Saker Falcons (more on that later), who became our dear friend. The day was taken up with securing travel permits, exchanging currency and buying supplies. I am surprised we are not taking any food from Ulaanbaatar. Luis tells me to expect extremely rough conditions. Luis and Lowell are very experienced and determined field scientists, so I am sure we are in for a very rugged trip. On a previous Mongolia expedition with the American Museum of Natural History, Luis and Lowell and their group had mostly gone hungry, losing significant weight. Conditions were much worse in Mongolia in those days, shortly after the USSR collapsed and Mongolia became independent again.

The stores in Ulaanbaatar do not have much variety, but Lowell and Luis do not intend to take many supplies. We will buy food from the nomads in the Gobi. I look in vain for an extra couple of bottles of Jack Daniels, and am very pleasantly surprised when Lowell shows up with them from somewhere. I am anxious to leave Ulaanbaatar for the Gobi. I was very favorably impressed that Ulaanbaatar lacked any McDonalds or other chain stores or restaurants. Won’t be long, though.

Batdelger is very helpful. He is short, strongly built, friendly, open face and smiles often. He works at the museum as an ornithologist and is an authority on Mongolian birds. He is especially fond of the Saker falcon, used by the Arabs in the Arabian Peninsula as hunting falcons. I hear a good falcon can bring thousands of dollars. Arabs come to Mongolia from Saudi Arabia and the GCC (Oman, Dubai, Abu Dhabi, etc.) to collect them, and they are becoming scarce. Batdelger especially wants to count the numbers of Saker falcons as we travel... Art

August 9 Rising at 5 am, we gathered up our gear and headed out to the airport to catch the 8 am flight to Hovd. Checking in was a bit of a challenge due to all our camping and collecting equipment. After extended negotiations, Batdelger and Luis were able to compromise on a fee of 200,000 togrogs (about $200) for the excess baggage. In the waiting lobby, we happened to sit next to a Kazakh family returning home. It was a bit of a toss-up as to whether we found them to be more foreign or they found us to be so.

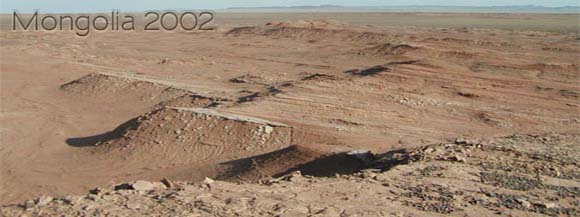

In any event, the 3-hour flight went off pretty much as scheduled. As we headed west, occasionally densely forested mountains and hillsides gave way to much more sparsely vegetated desert mountains and rocky valleys. Upon nearing Hovd, two, large, lakes came into view, sapphire jewels set among the brownish gray plains and black mountains.

After rounding up our gear, we checked in at the local hotel and spent the afternoon in a renewed series of meetings. As feared, the roads out of Hovd were closed due to the hoof-and-mouth quarantine, and we would have to get special permission from the mayor and the health commission to get out. First we introduced ourselves to the rangers who ran the preserve in which Tatal, the fossil locality that we hoped to explore, is contained. Without too much trouble, we were able to pay for a permit to do what we wished, assuming we could get out of Hovd.

The key to that magic trick came when Batdelger tracked down the brother of the mayor, Uuslie, who worked as a driver. (He spelled his name various ways in English; Art's notes use an alternative spelling.) We quickly hired him to be our driver, after he "promised" to help us get the permits required to leave Hovd. Exhausted, but satisfied that we were on the right track, we crashed after dinner without much fanfare... Lowell

August 10 In the brisk cool air of a Mongolian morning, we rode with Uuslie to the city's open air market to buy food and some last-minute cooking utensils. We hoped to make it out of town later in the day, and prospects for that improved dramatically when Uuslie was able to help us get the necessary papers late in the morning. By early afternoon, we seemed to have everything necessary and headed out, but at the city limits, we were confronted with a police checkpoint.

The checkpoint consisted of several gers, round tent-like structures, and a cement-block garage, most of which were hooked up by hoses to oil drums containing insecticide. In order to get out of Hovd, Uuslie would have to have his van, a Russian version of a VW van, fumigated by leaving it in the garage for 40 minutes. In addition, we all had to strip down to our shorts and sit in one ger while our clothes were fumigated in an adjacent ger. Since others were in line in front of us, the whole procedure took about an hour and a half.

Finally, after getting water at a local spring, we left Hovd in our rear-view mirror, driving along an idyllic stream, which meandered across a broad plain rimmed with dark, rugged mountains. Eventually, we approached one of the immense, sapphire-tinted lakes, Har Us Nur or Black Water Lake, which we had seen on the flight in. Imposing golden eagles and other raptors sat atop several of the utility poles that ran along the shoreline.

As we approached the small town of Durgon, we veered off the road and drove several miles across a gently inclined, grassy plain, where we set camp as night descended. We cooked a quick dinner and laid out our sleeping bags on the ground under spectacular, pristine skies, intermittently laced with technicolor meteors. But unfortunately, the mosquitoes, gnats and flies who had joined the celebration of our first night in the field were more intent on partying than we were…until about 3 am... Lowell

August 10 I got up early and took a walk around town at sunrise. Hovd has one paved main road, all the side roads are dirt. It is amazing, this tiny little town, with a single power and telephone line, but you can connect to the Internet in the post office! Luis went and checked his e-mail. Luis is a loquacious, gracious Argentine, invariably cheerful. I found a Buddhist temple and gave the prayer wheel a spin for our expedition. Only saw one man with a donkey cart out at this hour. I hope we can get the bloody permit; the return flights to Ulaanbaatar are full for the next week, and the prospect of staying in this little village is not appealing. Batdelger found the mayor’s brother, and Luis and Lowell have offered to hire him and his vehicle, a Russian 4x4 that looks like a VW van, called a Burgon. I thought about painting flowers and a peace sign on the side, for nostalgia’s sake. Lowell and I were students at UC Riverside during the flower-child age in California. Those were the days.

We went to a fabulous open-air market to shop for supplies; cooking utensils, pots, carrots, onions, potatoes, pasta. The market had cattle, camels, horses, and sheep for sale, even new colorful wooden supports for a ger. I wish I could take a ger back to Texas with me. There were Mongolians in all manner of dress, some wearing the traditional robes and boots with turned-up toes, like Tibetan monks.

Our driver’s name, as near as I can tell, is Uutzi or Urtzi. He seems pleasant enough, speaks no English. When we get back to the hotel, good news! We got the permit, and we can leave! We will travel north to Durgon, spend the night, then on to the field area we want to prospect in the Tatal Mountains.

A short distance out of town we ran through the disinfection station, and were required to strip down to our shorts and hand over our clothes for disinfection. They even sprayed the inside of our mouths with some foul liquid. The vehicle went through its own disinfection tent.

Finally, on our way, drove for hours through the rolling dry grass-covered steppes and around a beautiful blue lake to the small town of Durgon, a collection of gers and wood shacks with corrugated metal roofs. There is a small square in the town center, with 8 or 10 pool tables in various stages of deterioration, with men crowding around them. A curious crowd gathered around us, and we give candy to the children. The Mongolians are invariably friendly; they remind me of American Indians in appearance. Of course, they are distantly related. We saw eagles and a Saker Falcon on the power lines along the road.

We camped a couple of kilometers outside the village and prepared dinner. We gather camel poop for the camp fire, no wood, trees or shrubs anywhere. We forgot to get any plates or bowls, but we improvised. Dinner was an onion and tomato mixed salad (the last vegetables we would have for a while), and pasta with butter and chile sauce. Luis Chiappe is an accomplished field chef. The first night under the stars was magic; the Milky Way and stars brilliant above. We turned in without tents, in order to get a quick start in the morning. Mosquitoes were a bother here, but I was so pleased to be camping in the Gobi, in good company and with an adventure ahead, I took little notice... Art

August 11 First thing, we drove back into Durgon to register with the local authorities and meet with the supervisor for the Har Us Nur region at their small government visitor's center. Then, we embarked on a day-long odyssey in search of Tatal.

After traversing a mountain pass to the NNE of Durgon, we entered a rather large valley that contained a gaggle of gers nestled a ways away from another strikingly blue lake. The locals claimed to know where Tatal was, but the 18-year-old boy who offered to show us took us to a large cut bank along a dry river bed. The beds exposed in the cut were recent floodplain sediments; no dinosaurs there…

So, we decided to strike out on our own using Barsbold's directions and the geologic map he gave us. About 20 km west of the lake, we finally found some outcrops composed of reddish brown silts and sands covered with a layer of limy mud that was chock-full of burrows. The silts and sands had been deposited by an ancient stream across a fairly gently sloping floodplain about 113 million years ago, and the hardened, limy mud was probably deposited in a shallow lake inhabited by numerous burrowing organisms. The gray layer of burrowed mud was so hard that it formed a small plateau on the top of the small bluffs that rimmed the small, modern drainages of the area. One bed of pebble-rich conglomerate near the base of the bluffs contained several scraps of broken dinosaur bone, but the pebbles in the ancient stream seemed to have destroyed any recognizable skeletons that had fallen into the ancient stream.

There were some more, smaller outcrops of the same rock layers off to the west a ways, but we could not find fossils there. Nonetheless, we were convinced that we had finally found the right area, and so we returned to the gers by the lake to set camp and rest up for more searching and exploring on the following day. The folks in the gers kindly hosted us with a meal of fried bread, tea, and milk tea... Lowell

August 11 We got up at first light, ate hard Mongolian bread and tea for breakfast and returned to Durgon. We will try to visit the very picturesque Buddhist temple or lamasery perched on a hill just outside town. Luis and Lowell went to see the village head man to get a permit to enter the protected area we would explore. We got the permit, and remembered to get some plates and bowls at the tiny little store in the village square. It appeared the same crowd as the day before was playing pool. Why it is that teenage boys everywhere look surly while playing pool? We stopped at the lamasery, but could not get in, it was a holiday and apparently the Lama was not in.

Finally we are off to find the outcrop near the village of Tatal, driving hours along a gravel track through a mountain pass. We stopped at some gers gathered on a slope of a large valley with another gorgeous dark sky-blue lake in the distance. The lakes are shallow and saline, and have no fish. They do produce a lot of mosquitoes. The area reminds me of the Basin and Range area of Nevada, semi-arid with scattered saline lakes. I had the fabulous experience of entering my first ger as we stopped to ask directions. The custom is to enter through the opening and move around to the left. There is a cooking circle in the center, usually with a small iron stove, and ledge or bench around the circumference for sitting and sleeping. It is considered a major social gaffe to walk through the center of a ger.

We were offered camel milk tea, which is definitely an acquired taste, and hard (very hard!) fried bread. The ger is neat and clean, with a dirt floor covered here and there with a small colorful rug. Luis had advised me that courtesy required one to drink or eat whatever was offered, no matter how disgusting. Luis and Lowell told tales of previous Mongolian expeditions where the obligatory drink had caused them immediate and spectacular intestinal distress.

The Mongolians will also often offer snuff from a small onyx bottle wrapped in colorful silk cloth. The bottle has a stopper with a tiny spoon at the end, and one snorts the snuff, just like English nobility in the movies. I was never sure what the exact composition of the snuff was, but it had no noticeable affect. The inside of the ger invariably smells of mutton, often hanging in strips to dry on the walls. The ger itself is made of sheep felt, and their bread is deep-fried in mutton fat. (At this writing, it is more than a year after the expedition, and my backpack and sleeping bag still smell of mutton). Batdelger asks the way to Tatal, and we took a teenage boy with us who said he knew the way.

We meandered around in the desert for a while and came upon a truly macabre scene in a small draw. There were hundreds of skeletons of sheep, goats, camels, horses and cattle scattered and mingled in death on the slopes of a box canyon. At the head of the canyon, there was a large lean-to shelter made of wooden beams, perhaps 50 meters long and 5 meters deep. It appeared to me that Mongolian herdsmen had probably burned diesel in the four or five 50-gallon barrels in front of the shelter to keep their herds from freezing. The ground was scorched for several meters around the barrels. Batdelger says last winter was severe. It must have been horrendous. Standing there in the 100 degree heat, it was hard to imagine the 40 degrees-below-zero winter, with freezing Siberian winds howling down the steppes.

After some wrong turns and confused directions from the locals, we finally reach Tatal and walked the outcrop checking for bone, but did not find anything. It felt great nevertheless, to be walking on Cretaceous dirt, looking for dinosaurs!

Returning to camp, we pitched tents in a wide draw on the rocky slope of a small hill near a collection of three or four gers. Batdelger does not seem to hold up in the heat, he appeared tired and although always cheerful, was a bit quiet. Our driver is rather quiet. His name, as near as I can make out, is Urtzi. We drank camel milk tea from small bowls with the headman in his ger. Camel milk tea is a little salty, and definitely is an acquired taste. Lowell and Luis were disappointed that the outcrops at Tatal were not more extensive... Art

August 12 In the morning, we discovered that our extensive wanderings on the previous day had left us with only 80 liters of gas in Ulzie's van. So, after consultations with the locals, the morning involved driving to the small village of Zavhan NE of camp in search of gas. While stopped at a local village near the lake east of camp, we enlisted the help of the village patriarch, who claimed to know where the Russians had collected fossils of Neogene mammals along the shore of a nearby lake called Togoo Nur.

After a short drive to the site, we spent a couple of hours prospecting along terraced outcrops of cream-colored sands and silts that rimmed the lake shore. Fossilized fish vertebrae were abundant, and each of us found a rodent jaw. Other fossil fragments that we found once belonged to the foot of a medium-sized carnivore and a vertebra from an ancient relative of elephants.

Around noon, we headed on to Zavhan, where we fortunately found gas, as well as some water and other food supplies. One rather odd moment occurred when an apparently angry local man tried to ride his horse up the steps of the town hall in order to lodge a formal complaint with the government. However, the horse seemed to think better of it, and refused to climb the steps. We never found out about the eventual outcome.

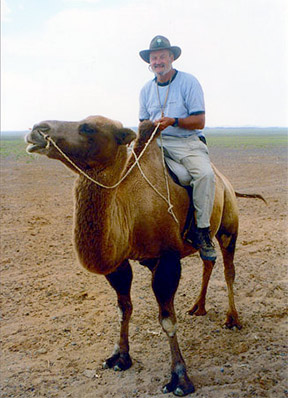

Back in gas and drinks, we began the return drive, and came across a large flock of 12-15 griffin vultures scavenging a camel carcass. While dropping off the patriarch back at his village, the community invited us to ride one of their camels. In turn, we handed out candy and wafers to the kids.

Finally, retracing the route we took yesterday, we passed the outcrops we had encountered yesterday and continued on another 8 km to the west, where the rolling hills of low shrubs opened up into a modestly large patch of reddish-brown badlands. The rock layers we encountered were basically pretty similar to the ones we had seen the day before and again represented a floodplain environment. To our delight, both Art and I found fragmentary fossils of the flying reptiles called pterosaurs, including part of a lower jaw with teeth and a hollow hip bone. However, in less than two hours, we had pretty much covered the exposures, which contained a sequence of rock layers about 100 feet thick. So the area wasn't really large enough to support a major expedition.

Nonetheless, we were encouraged and returned to camp about 7 pm, where Batdelger prepared a celebratory stew that was cooked in a milk can containing water, mutton, potatoes, carrots and turnips, which was boiled by throwing heated rocks into it from the fire pit. It proved to be an excellent meal, enjoyed under a dark canopy of the heavens laced with shooting stars... Lowell

August 12 During the night, I awoke to the sound of the pounding of hundreds of hooves. It must have been 3:00 a.m. or so. I awoke at first light to a wonderful sight; the gers were backlit by the soft morning sunrise reflecting off the distant lake, and the gers were surrounded by the huge herd of sheep, goats and Bactrian camels which had arrived during the night.

Lowell and Luis want to go check another portion of the outcrops we visited yesterday, about 28 kilometers north. On the way there, we would pass a dry Neogene lake near the lake we can see in the distance, Lake Togoo. We stop at fairly large collection of gers, perhaps 20 or so. Batdelger speaks with the headman, and he tells Batdelger that there are large bones in the Neogene outcrops. We take the headman with us, he smells like rancid mutton, but is friendly and helpful.

We stop at the Neogene exposures and walk the outcrop. I immediately find a packrat tooth (Neotoma sp.), probably the only critter I could identify, since I was so familiar with them from my Pleistocene fauna in Death Valley, California. We spent some time digging around a mammoth vertebra, but left it in the ground and continue on. We need gasoline, and we are 50 kms. from Durgon. In this country, 50kms. is about a four-hour trip. There is another village closer, about 20 kms., Zavhan. Zavhan is more or less on the route we want to travel, while Durgon would require us to backtrack. The headman tells Batdelger that Zavhan “sometimes” has gasoline. Luis and Lowell confer, and they decide to push on to Zavhan.

I remind Luis and Lowell that the headman had said Zavhan “sometimes” has gasoline. If we arrived there and there were no gasoline, we would have to stay there until gasoline arrived, no telling for how long. I was genuinely concerned, but Luis grinned broadly and told me indulgently “Art, in this business, we take risks”. These guys are crazy. This country is very wild, and we are a long, long way from any possible help, and have no way to communicate with anyone.

We arrive at Zarhan, a dusty collection of gers laid out in more or less straight rows, and a few wooden or adobe huts on the main drag. We found the “gas station”, a beat-up old hand-cranked pump and it had gasoline, much to my relief. We buy some cookies and water at a small store. I bought a Mongolian hat. We pressed on to the outcrop, pleased to have a full tank.

Lowell and Luis are not that impressed with the Cretaceous outcrop, but we prospect it for bone. Lowell and I each find Pterosaur bone, but no dinosaurs.

We drop the headman off at his village on the way back to our camp. He invites us to take a ride on a Bactrian camel, which Luis and I do, the entire village is gathered watching, and find our camel-riding technique hilarious. We took group photos with the entire village.

Dinner this evening was an experience. We had purchased a side of mutton at Durgon, and we carry the meat in a muslin sack. I am amazed, the meat lasts OK for four days in this heat; we have no ice, of course. On the fourth day it acquires a little extra flavor. Tonight we had to cook all that remained on the bone of the mutton, and Batdelger and Urtzi said they were going to cook Mongolian style. They had boys gather us a large sack of dry camel droppings from the desert. They put the poop in a fire pit, more or less 12-18 inches deep, and put fist-size rocks into the burning camel poop. They prepared a pot with water, carrots, potatoes, and onions. The remaining mutton was just a little meat hanging on the bones, which they broke to expose the marrow, and put it in the pot. They did not put the pot on the fire.

When the rocks were red-hot, they fished them out of the camel poop and plopped them directly into the pot, which was soon boiling. It was delicious; I guess the camel crap adds a little flavor... Art

August 13 After studying the geologic map that Barsbold provided, we realized that there were still a couple of outcrops that we had not yet visited. Using the latitude and longitude for those sites on the map, we tried to drive to them, using our GPS unit to guide us. Following an extremely bumpy, cross-country ride, we managed to locate the remaining, mapped exposures. At both sites, we found a good deal of fossil wood but few bones. Generally, the rock layers looked similar to those of the Tugulu Group that we had seen on the previous two days, and they appeared to represent the same floodplain environments. Yet, although there was probably a 150- to 200-foot-thick sequence of sandstone and mudstone layers exposed over a 1- to 2-square-mile area at one of the sites, it still wasn't a large enough area to support a full field season of work, especially with bones being so sparse.

By late afternoon, we had covered the two areas and returned to camp, where we bought a sheep from the locals and invited them to dinner. They slaughtered it for us in typical Mongolian style, then watched in amazement as we barbecued it over an open pit fire, just like Luis would for an Argentine asado.

Once the crowd had eaten its fill and dispersed back to their gers, we decided to embark the next day to check out some other fossil sites across other regions of western Mongolia. It would be another very wild ride... Lowell

August 14 As the sun rose, we said our farewells to our neighbors of the last few days and broke camp. Our plan was to head toward the camp of some Japanese colleagues, who were working a couple hundred miles to the south near the small town of Darvi.

Clearly, it was going to be a hot day of driving, and the stunningly blue waters of Har Us Nur looked pretty inviting. About lunchtime, our road began to wind alongside a small river that connected Har Us Nur and Har Nur. Having not showered since we left Hovd, we decided to take a dip. The cool water and gentle current quickly soaked through the sweat-caked, Cretaceous dust that coated our bodies. After dousing ourselves sufficiently, we ate a picnic lunch by the river, swatting at the pesky, biting flies and gnats that wanted to join in the festivities.

Finally refreshed, we headed on south to Darvi-Hovd, where we arrived as the sun was setting. We booked a couple of rooms in the town's hotel for about $2.50 per person. The rooms were decently comfortable, but the bathroom was a wooden shed out back... Lowell

August 13 We drove to a Jurassic section and prospected, found only petrified wood, no bone, then onto the middle section of the Cretaceous outcrop. We drove miles up and down the basin, exploring the scope of the outcrop. Lowell and Luis are not pleased with the extent of the outcrops or the richness of its fossil content. They are talking about maybe going back to Hovd to get a flight back to Ulaanbaatar. We stopped for water at a well near some gars, and a Mongolian horseman who was tending a mixed herd of camels and horses rode over to us. He completely ignored us, seeming to just want to relax in the shade of our vehicle and smoke his pipe.

We returned to camp and purchased a sheep, which the Mongolians slaughtered for us Mongolian-style, which was quite a scene. Mongolian Buddhist culture considers it disrespectful to kill and spill blood on the ground. So they place the sheep on its back, make an incision in the belly, stick their hand in the chest cavity and hold the critter’s heart until it expires...

hat evening Luis made an Argentine style churrasco, wrapping mutton with potatoes and carrots in aluminum foil, then placing it in a hole with the camel-dung fire, covering it with dirt, then another camel dung fire on top. It was wonderful. We were joined by some Mongolians, very friendly and curious.

One of the Mongolians informed Batdelger that the hoof-and-mouth disease in Hovd was now very serious, and no one was allowed to leave. We will not be able to return to Hovd for the return flight to Ulaanbataar, since we could be stuck there for months. We are discussing either driving to Ulaanbaatar, or catching a flight from Bayanhongor. Either was is OK with me, flying back now would give me more time in Beijing where I hope to visit friends, but I would rather have the adventure of crossing Mongolia in the Russian 4x4. Luis decides to try to find the camp of a Japanese paleontologist colleague and perhaps a Cretaceous outcrop at Boon Tsagann Nuur where a unique fossil bird (Ambiortis sp.) had been found by a Russian expedition. The camp is in a mountain range called Darvi Altay... Art

August 14 We drove more than 200 kms. on a simple rutted dirt road and finally make it to the small town of Darvi Hovd, which sits in a valley at the foot of the Darvi Altay range. I am absolutely amazed that the country is beautiful, but totally empty, we saw nobody for the whole distance. Just outside of Darvi Hovd, we cross a river, and stop to bathe in its clear water. I saw my first yak, and took its picture. I had always wanted to see a yak since reading a Donald Duck story about Tibet when I was a kid.

We found a hotel; it had no bathroom and the rooms are 2500 Tugregs, more or less $2.25! It did have a pool table, which appear to be the major entertainment in rural Mongolia. The bathroom is a really fragrant wooden outhouse behind the hotel. Urtzi will sleep in the vehicle, afraid of thieves. We have become good friends with him, somehow managing conversations with gestures and “Mongenglish”. Jack Daniels improves our fluency, we find... Art

August 15 It was a short morning's hop from Darvi Hovd to Darvi Altay, where we arrived about lunchtime. While eating in a small restaurant there, we inquired about our Japanese colleagues and found out that you could see the large white tents of their camp perched at the base of the mountains about 6 miles to the southeast atop a massive alluvial fan.

After bouncing through the rivulets incised in the alluvial fan, we arrived at their camp just after they had set sail up the canyon for their afternoon's work. In hot pursuit, we raced up after them, through striking and steeply tilted layers of brownish gray mudstone and sandstone. These rocks were slightly older than the ones we had been working in, dating from the Jurassic Period. Finally, after getting close enough to them that they heard us honking, we caught up and had a nice conversation. They were in the process of excavating some dinosaur bones. They suggested that we drive further east, where there were some more exposures of early Cretaceous rocks in Byanhongor Province.

Appreciatively, we parted to retrace our path to Darvi Altay from where we could get gas and more easily head east toward the relatively large city of Altay. As the late afternoon turned to evening, we lumbered up and through a rugged mountain pass and descended into the bright lights of Altay, where we were lucky to find a couple of rooms in the upscale Altay Hotel…complete with bathrooms... Lowell

August 16 Our goal was to get close to a site that the Russians had worked several decades ago that produced some fossils of Mesozoic birds. Being a specialist in this topic, Luis was quite determined to try to find them; however, we did not have good data about exactly where the site was. Would it end up to be a wild goose chase? Only time would tell.

This first day involved a seemingly endless drive over relatively flat dusty tracks that set off from Altay cross-country toward Bat Tsaagan near the west end of Boon another lake named Tsaagan Nur.

About midway through the afternoon, we had a flat and discovered, to some consternation, that Ulsie did not have any spare tire that could hold air. Fortunately, however, we did have a small kit to patch tires, a process that took a couple of hours. Once we were back in motion, we came across a pair of men on a motorcycle sitting aimlessly along the side of the road. It's customary in such circumstances to ask if any help is needed. They had run out of gas, so we bartered some of our gas for a few bites of cooked marmot meat, which served as our afternoon snack. By evening, we could see the western shore of the lake in the distance and decided to set camp far enough away to avoid the mosquitoes... Lowell

August 17 After Batdelger fried some bread for breakfast, we set out to try and find the early Cretaceous bird site that Luis hoped to see. We loaded the coordinates for the general area our Japanese colleagues had given us into our GPS in hopes of getting close. Our rugged route took us up a boulder-strewn wash that drained a mountain range of picturesque metamorphic rocks to the west of Boon Tsaagan Nur. At one point, when we stopped to stretch our legs, Batdelger found a pile of wolf scat among the rocks. The landscapes were spectacular as we drove through the increasingly narrow drainages that eventually led to a pass, which allowed us to descend along the south side of the range. Unfortunately, none of the rocks we saw were sedimentary; all were metamorphic.

Stopping at a bevy of gers high on an alluvial fan on the south side of the range, we met an old man who said he knew generally where the Russians had worked, about 50 km to the south past the next range over. After filling up our water containers at their well, we continued our trek with the old man in tow as our guide. He directed us around the east end of the next range and up along a steep rocky ridge, where one of his cousins lived. She said she remembered the Russians working nearby in the 1980s, but she didn't know exactly where. Although we found some sliced-up gray limestones, we couldn't find any gray shales like the ones that contained the bird fossils.

With no fossils to be found, no spare tire, and a dwindling supply of gas, we left the old man at his cousin's, as he wished, and headed back toward the town of Baat Tsaagan along the eastern edge of Boon Tsaagan Nur. We got there about 4 pm and succeeded in finding some gas, but we were having problems with water condensation in the fuel line, which took about an hour to clear out.

Our search for fossil birds had turned out to be quite a wild goose chase, so we decided to cut our losses and head toward Bayanhongor... Lowell

August 16 Leaving Darvi Hovd, we wound our way up the slope leading to the Altay Mountains. We found the Japanese expedition, their camp was amazing; generators, a mess tent, showers, tents laid out in neat lines. Lowell says they are very well funded by a corporate museum in Tokyo. They were collecting a duckbill dinosaur (hadrosaur), and seemed a little secretive to me. We had hoped they would invite us to dinner, but had no luck with that, so we continued our trek to the village of Altay.

After a very long, tiring drive on a dirt track (we have seen no pavement since leaving Hovd), we arrive at Altay and find a run-down hotel. I am feeling a little ill, feels like a cold coming on. I am bone-tired, and we are all beat up from bouncing around in the Russian 4x4. If it has any springs, they are ineffective. Worst of all, the Jack Daniels is almost gone. We are at 2300 meters altitude here, and it is a little cooler... Art

August 17 I awoke late, at 0830, still tired. Luis still wants to find the Cretaceous outcrops where the Russians found the Ambiortus, near Boon Tsagan Nuur. We find the local market, and buy some supplies, especially veggies. To now, our diet has consisted largely of mutton and bread deep-fried in mutton grease. We will head out south, south-east to look for the outcrops.

We are heading towards a mountain range visible in the distance. On the way, we had two flat tires, one tire completely trashed, and Urtzi repaired the spare tire with a hot patch. We are at least a hundred miles from any town, going over a saddle between two mountains, no spare tire and gasoline running low. Luis and Lowell are determined to get to the outcrop, but this situation is precarious. Lowell tells me “no problem, if we lose another tire or run out of gas, we will just rent camels and ride out”. Lord have mercy, these guys are really crazy.

We camped this evening on a huge plain between mountain ranges. We have arrived at Boon Tsagan Nuur, which Batdelger tells us means “big wide lake” in Mongol, and indeed, there is a large wide lake in the distance. The night sky is absolutely clear and we watch satellites passing overhead in their orbits... Art

August 18 The drive to Bayanhongor went smoothly. About half way there, we passed a flock of about 70 vultures trying to feed on a camel carcass. Batdelger took his knife and cut slits through the tough hide in order to make it easier for the birds to feed. After photographing the scene, we continued on toward Bayanhongor and arrived about 1 pm. We checked into a hotel, where Art was unanimously voted into the presidential suite, complete with "luxurious" shower sporting wonderfully hot water. In addition to a jaunt through the local open market, much of our time was devoted to trying to exchange our airline tickets for the return flight from Hovd for tickets from Bayanhongor to Ulaanbaatar... Lowell

August 18 After a breakfast of fried bread and tea, we broke camp and headed for Bayan Khongor, and arrive in the late afternoon. We find the hotel and Lowell and Luis kindly insist that I take the only room that has a shower, and I offer token resistance. We are all very tired and beat up. That evening, Lowell and I share the last of the Jack Daniels with Urtzi. I think we also celebrated with some Mongolian vodka. We were successful in catching a flight, and said good-bye to Urtzi. The Russian turboprop airplane’s tires are bald, with the fiber showing through... Art

August 19 The ticket exchange was finalized in the morning, and we said goodbye to Ulsie, who headed back to Hovd after dropping us off at the airport. Once again, we had to negotiate the fees for excess baggage, but finally everything was arranged. Our flight took off at about 3:30 pm. The first leg to Arvayheer was very turbulent, and, for some reason, the air conditioning was not working. Temperatures shot up to about 100 degrees F. Fortunately, the flight was only about 45 minutes long.

In Arvayheer, we all got out of the plane while the ground crew refueled it, and while walking around on the tarmac, we noticed that the plane's front tires were bald with patches of the mesh underlying the rubber showing through. The pilots nonchalantly inspected them and simply laughed off the problem. So, with our fingers crossed, we reboarded.

Despite our apprehension, the final leg to UB went off without a hitch, and we landed in the late afternoon. Fortunately, there were rooms at our hotel, so we ate dinner at a local Indian restaurant and hit the sack exhausted... Lowell

August 20 Having returned a bit earlier than we had anticipated, we met the next morning to regroup. Art changed his return ticket to Beijing for the next day, and Batdelger suggested that we celebrate Art's last day of the trip by going on a marmot hunt. So, in the afternoon, we drove about 50 km south of Ulaanbaatar to the ger of some of Batdelger's relatives. After introductions, Batdelger's cousin loaded up his 1950s, 22 caliber rifle, complete with long tweezer-shaped supports on the front for steadying it, into our van. As we drove through the grassy hills, we saw lots of marmots, but apparently none large enough to shoot and cook. Finally as the sun set, we gave up and returned to UB unsuccessful in our big game hunt.

Somehow, it seemed a fitting end to the trip; for, although we had see a good deal of spectacular country and had an adventure that none of us would ever forget, we had precious little success finding what we were looking for. Sometimes in paleontological prospecting, that's just the way it is, despite the best efforts of everyone involved... Lowell.

Post Script Shortly before publishing this account on the Infoquest website, we were very sad to learn that our fellow adventurer Usslie from Hovd tragically died in a car accident on his way back to Hovd. Batdelger also died of a heart attack the year after the expedition.

p>

p>