Discoveries in China

Dinosaur Quest in China: The 2000 Expedition to Xinjiang with Dr. Lowell Dingus

I could hardly believe my good fortune. A remote landscape long steeped in mystery to westerners, the province of Xinjiang in northwest China also represents a treasure chest for paleontologists. Since I first began my career as a paleontologist, I had always wanted to explore its desolate badlands. In the summer of 2000, I finally got my chance as part of an expedition sponsored by the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County.

My chief colleague on this trip was Luis Chiappe, chairman of the Department of Vertebrate Paleontology at that museum and a close friend with whom I had worked in Mongolia and Argentina. Our goal was to find dinosaurs, especially ones that might shed new light on the origin of birds. Luis is one of the world's foremost experts on that subject and China has recently become a focal point for such research as the result of spectacular new discoveries of feathered dinosaurs and primitive bird fossils at Liaoning in northeast China.

Working with funds provided by the InfoQuest Foundation and the National Geographic Society, we set out with a team of expert fossil collectors and geologists from the LA County Museum, Montana State University, the University of Nebraska, and other institutions in Argentina and Italy. It would prove to be a memorable adventure.

August 16-19 -- Getting to Beijing With Luis having already gone ahead to set up our base of operations and begin prospecting for fossils, David Loope, Elizabeth Chapman and I flew to the capital of the People's Republic, Beijing. David is a professor of geology at the University of Nebraska who had helped us on both expeditions to Mongolia and Argentina.

As noted in other accounts on this web site, his insights unraveled the mystery of how the spectacular fossils from the Gobi Desert of Mongolia came to be preserved. Avalanches of wet sand slid down the steep faces of immense dunes more than 70 million years ago and buried the animals. His observations in Patagonia helped clarify that the arid climate there was seasonally disrupted by periods of high rainfall, which caused the floods that buried the dinosaur eggs and embryos.

Elizabeth formerly worked with both Luis and me at the American Museum of Natural History, where she helped us publicize our research in Mongolia and announce our discovery of the first-known sauropod embryos from Patagonia. A life-long amateur paleontologist, Elizabeth couldn't wait to participate as a full-fledged member of a paleontological expedition, even though she had briefly visited us when we were collecting fossils in Mongolia and Argentina.

Beijing is the thoroughly modern capital of a vibrant and rapidly changing society. In many ways, it reminds me of the city in which I was raised, Los Angeles. Although the air is usually polluted and the streets and freeways are choked with vehicles, many inhabitants seem to be reveling in their newly found material comforts and somewhat relaxed social freedom. Malls and department stores abound, and cell phones have proliferated across the sprawling urban landscape.

As Elizabeth, David, and I explored this modern landscape, while adjusting to our jet lag, we were most struck by the juxtaposition of the old and new buildings. Behind the modern facade presented to those traveling the main streets of the city, ancient neighborhoods with twisting streets and densely packed small dwellings lurk in the middle of many major blocks. So, although the skyscrapers immediately attract your eye, a visit to the city is not complete without a walk behind the scene in the hutangs. The architectural jewels of past Chinese civilizations reinforce the antiquity of the rapidly disappearing hutangs. Chief among these monuments is the Forbidden City, where emperors and their courts of previous Chinese dynasties lived and ruled.

I feel most fortunate to have witnessed the dramatic transformation of the country that has occurred over the last 15 years. I first visited Beijing in 1987 to help arrange for an exhibition of Chinese fossils that traveled to the American Museum of Natural History in New York. At that time, few skyscrapers had been built, and few modern department stores or malls adorned the major streets. Most shops consisted of small stalls that lined the sidewalks. But over the years, as the economy grew and the merchants became more affluent, they moved from their stalls into street-front stores, which they have now renovated and illuminated with brilliantly flashing neon signs.

This all is not to say that social and political problems have been eradicated, far from it. Poverty and instances of political repression still remain. Continued progress toward a more open and free society will almost certainly be fraught with momentous difficulties, but we in the United States have a deeply misguided view of the present situation in China. Most of its citizens are quite friendly and anxious to interact with Americans. Many are willing to openly discuss their own country's problems, and they are intrigued by our country's success and current events. It strikes me that the peoples of our two countries actually share many more common goals than differences of opinion.

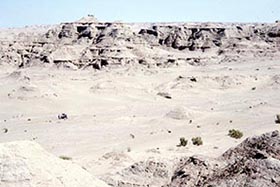

August 20 -- Urumchi But our agenda entailed exploring inhabitants and events in China that occurred long before human civilization originated. So, after a couple of days roaming about Beijing, we boarded an airliner for the three-hour flight to Urumchi, the capital of Xinjiang Province in the northwest corner of the country. The sights on the flight were incredible. We flew over the parched southern margin of the Gobi and along the northern flank of the majestic Tian Shan Range as we approached Urumchi. The stately peaks of these mountains rise up over 20,000 feet, and the contrast between their forested slopes and the sparsely vegetated wastelands of the desert stunned our visual senses. August 20 -- Urumchi But our agenda entailed exploring inhabitants and events in China that occurred long before human civilization originated. So, after a couple of days roaming about Beijing, we boarded an airliner for the three-hour flight to Urumchi, the capital of Xinjiang Province in the northwest corner of the country (slide 3). The sights on the flight were incredible. We flew over the parched southern margin of the Gobi and along the northern flank of the majestic Tian Shan Range as we approached Urumchi. The stately peaks of these mountains rise up over 20,000 feet, and the contrast between their forested slopes and the sparsely vegetated wastelands of the desert stunned our visual senses.

When we landed, we were met by Luis and Ji Shu'an, a student at the National Geological Museum in Beijing who would serve as our colleague and translator during the expedition. We were pleased to hear that the crew was already thoroughly settled in a small hotel near the field area and that they were already finding intriguing fossils. After checking into a hotel, we went out on the street for dinner and ate in a small ethnic restaurant run by some of the indigenous local population called Uighurs. These people are distinctly different than the Han Chinese that populate most of China. They are Muslims who descended from some of the early inhabitants of the area, and their food is quite spicy but delicious. The dinner represented our first introduction to their culture, which we would encounter more intensely during our upcoming excursion to the area northwest of Urumchi.

August 21 -- Road to Karamay This day was reserved for the long drive to our field area. We began about 9:00 AM. Our trail led west on the main highway out of Urumchi, but our driver tried to take a shortcut and got lost in the dense agricultural fields surrounding the city. Although we were heading into the desert of the Junggar Basin, the area that we spent the morning driving through, just north of the Tian Shan Range and adjacent mountains, was quite well populated and cultivated. We drove along huge fields of fruit trees, tomatoes, melons, and other crops, irrigated by the gravelly rivers that drain the Tian Shan.

After about 100 miles of driving to the west, we headed north toward Karamay. The landscape turned much drier and evidence of agricultural activity diminished as the rivers dried up and the desert began to impinge in the form of large, ancient, sand dunes that bordered the highway. We stopped for a lunch of spicy chicken stew and tea at a small truck stop, where the proprietor of the restaurant loaded a Chinese-dubbed, American action video into the VCR for our entertainment.

Continuing north after lunch, we reached the dusty, oil town of Karamay about 5:00 PM, just in time to experience the city being blasted by small sand storm, whipped up by some approaching thunderheads. Karamay is essentially the county seat in the part of the province where we wanted to work. After winding our way through the dust-filled detours along the highway, which was being repaved and expanded, we continued north toward our destination of the tiny town named Urho, where we planned to spend the next two weeks.

We arrived about 7:00 PM at the only hotel in town, which would serve as our base of operations, to be greeted by the rest of the crew, who had already been there for about a week. After another fine dinner of spicy beef, chicken, fish, and vegetable dishes, we bedded down for the night.

August 22 -- Arrival in Urho We devoted our first day to a tour of the field area, beginning with a look at the exposures closest to Urho. The morning was cool and clear, with temperatures in the high 60's or low 70's. It took about 20 minutes to drive to the site in the two club cab trucks that Luis had rented to ferry the crew around to different localities. As we drove, we passed along tree-lined, dirt roads through the farmer's market and agricultural fields that occupied the small river valley in which Urho sits.

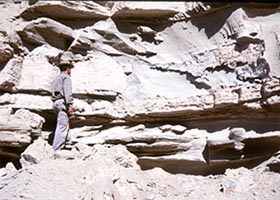

The closest outcrops formed the base of the sequence of rock layers that were exposed in the field area, and because they were the lowest layers, they were also the oldest layers, since rock layers are deposited one on top of the other. It was immediately clear from the rocks that they had been laid down on an ancient, gently sloping floodplain crossed by small streams.

The sandier layers were deposited by small, shallow streams, and the muddier layers were deposited when the streams flooded and overflowed their banks, carrying mud and silt out across the floodplain. The crew discovered fossils of turtles and a few fragments of dinosaur bones. We recorded the positions of these specimens using our GPS units, but did not spend time collecting them.

By late morning, the temperature rose into the high 80's, and we moved about a mile down the road to inspect some higher layers in the sequence. These were a bit different in nature, with thicker and coarser layers of sand, as well as finer layers of mudstone. The sand had been deposited by somewhat larger streams in sand bars, as the streams meandered across the floodplain.

As David, Luis, and I inspected the rocks, Luis's fossil preparator, Nancy Rauchenfaut, continued excavating a dinosaur pelvis she had discovered a few days earlier, and the rest of the crew prospected the outcrops for new fossils. By late afternoon, the temperature had soared into the low 90's, and the sun beat down relentlessly. We discovered some layers with abundant clams that had inhabited the ancient rivers, but no new good specimens of vertebrates.

About 7:00 in the evening, we were exhausted and returned to Urho, where I got my first good look at the town. As we walked along the main street, which served as the highway and constituted the only paved road in town, we passed by numerous small shops and restaurants run by a mixture of indigenous Uighurs and Chinese denizens. Many nodded and smiled politely, although they seemed a bit shocked to see westerners wandering through their town. After dinner, we went to bed to rest up for the next day's excursion.

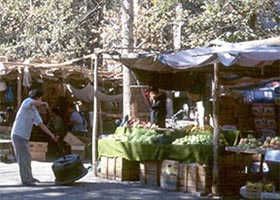

August 23 -- Initial Discoveries Elizabeth and Luis set out early to visit the farmer's market to buy some bread and fruit for our breakfast and lunch. In the early morning, the market is a beehive of activity, with merchants selling animals, butchered meat, produce, and almost anything else imaginable. After a brief breakfast on the back steps of our hotel, we loaded our gear into the vehicles and set out for field. We drove past the exposures where we had worked the day before and continued along the base of a shear cliff past the shoreline of dry lake bed to a set of outcrops on the far side of the basin.

Luis, David, and I continued our tour of these highest layers in the sequence of rocks, while the rest of the crew prospected for fossils. The crew had already discovered some noteworthy specimens in these beds. They included a small dinosaur skeleton, found by Ji Shu'an, which was covered with bony armor plates, and a nice pterosaur skeleton, discovered by Pablo Puerta, an expert collector from Argentina who had worked with us at the egg site in Patagonia.

This area had been explored about 40 years earlier by paleontologists from the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology in Beijing. The exposures covered an immense area, and we hiked a good five or six miles in order to visit all the sites. It was a grueling march, with temperatures approaching 95 degrees in the heat of the afternoon, but the character of the rocks was quite interesting. Occasional layers of purplish gravel and gypsum indicated that these rock layers had been deposited on a more steeply sloping and more arid landscape than the layers below.

The layers of gravel not only suggested that the currents in the streams were more swift and turbulent, but that there may well have been some hills or low mountains nearby. Nonetheless, the landscape was flat enough to play host to occasional ponds, which had been filled by finely banded layers of mud.

About 3:00, thunderheads moved quickly across the basin, and we were blasted by a small but violent sandstorm, with gusts approaching 50 or 60 miles an hour. Grit pummeled our faces as struggled back to our vehicles about 6:00 PM. By the time we got back to town, our spirits were badly buffeted. But the storm had abated, so we sat on the steps of the hotel, sipping cold soft drinks and beer to refresh our dusty bodies.

After a shower to wash the worst of the grime off, Luis, David, Ji Shu'an, and Alberto Garrido, a young geologist who works with us in Patagonia, reconvened with me on the steps to plan our strategy for measuring the sequence of rocks and collecting samples for scientific analysis. We agreed to begin the process the next day.

August 24 -- Dating the Rocks But Xinjiang had other ideas; for much to our surprise, we awakened to gray, cloudy skies and a light but steady rain. It had not been raining for long, but we were concerned that some of the specimens that we had begun to excavate might be damaged. Despite the risk of venturing out across the muddy roads in our trucks, which were not equipped with 4-wheel-drive, we quickly loaded up and bounced out to try and cover the specimens. Having secured the specimens under some tarps, we returned to town to wait out the rain at the hotel by doing some laundry.

Elizabeth took advantage of this break to do some shopping. It was her birthday, and she had received some birthday money to spend in whatever way she pleased. Not far from the hotel was Urho's only department store, so we decided to find her some unique treasures, not available back home, as mementos of her adventure. After surveying the possibilities, she decided on a few children's books about dinosaurs in Chinese and a host of mechanical insect toys to add to her collection back home.

After lunch, the rain had stopped, and we headed to the field about 2:30. David, Alberto, and I began our work in the middle part of the rock sequence. We knew from earlier research done by the Chinese paleontologists and geologists working for the oil industry that the rocks we were exploring dated from the early part of the Cretaceous Period, the last interval in the Age of Large Dinosaurs. This suggested that they were between about 90 and 110 million years old, but we wanted to pin down their age more precisely.

As Alberto and Dave measured the thickness of each layer and described the kind of rock that formed them, I collected small samples to analyze their magnetic properties. Such studies had proved important in refining the age of the rocks in Patagonia that contained the sauropod eggs and embryos, and we hoped that this technique would prove equally informative for us here.

I also collected samples to see if the rocks contained fossil pollen that might help us identify what kind of plants lived at the site and how old they were. It's a slow and tedious process to measure the layers and collect the samples, and before we could get magnetic data or look for the microscopic pollen grains, the rocks would have to be analyzed and inspected back in the laboratory.

By 7:00 PM, we had measured about 100 feet of rock layers in the sequence and collected several rock samples, so the crew headed back to town. That evening we celebrated Elizabeth's birthday at dinner. Luis had ordered a birthday cake from one of the local bakeries, and the hotel employees adorned it with candles. Elizabeth showed off her new toys by sending the mechanical insects scurrying across the dinner table, to the amusement of all in attendance. Despite being half way around the world in the rugged frontier of Xinjiang, it seemed that little in our lives had really changed.

August 25 -- Upper Rock SequenceClear skies returned, and after breakfast, we drove out across the basin to upper part of the rock sequence. Again, Dave and Alberto measured and described the rock layers, while I collected samples for magnetic and pollen analyses. We took care to plot the positions of where the crew had found fossils in the sequence of layers.

Meanwhile, Luis took the rest of the crew to some exposures off across the lake bed. It was rough going to get there because the dry lake bed was quite soft and bumpy, which made hiking across the mile and a half to the exposures very strenuous. Fortunately, the results were worth it. Luis, Pablo, and the rest of the crew found several good specimens of pterosaur skeletons and small crocodile skulls. But the heat of the day was withering, and by the time evening approached, we wearily stumbled back across the basin to our vehicles.

Back in town, we could tell that Ji Shu'an was a bit melancholy. It turned out that this day was his son's seventh birthday, and he was feeling a bit guilty about not being with him. Such moments of separation are a difficult, but necessary, part of fieldwork, and we had to do something to cheer him up. During dinner at a street-side table outside our favorite Uighur restaurant, we toasted his son with a favorite Chinese liquor called bijo. To the uninitiated, it's not very tasty, but for Ji Shu'an, it seemed to bring him closer to the celebration he was missing at home.

In the midst of our toasting, we were joined by the young son of the restaurant's owner, who came out to see what all the commotion was about. To encourage him to celebrate with us, we bought everyone ice cream from the nearby cart sitting just down the street. It was apparent that, to our young new friend, this was a truly rare treat; for, he proudly showed off his prize to all the people who passed by.

August 26 -- Dancing in Urho With the weather still cooperating, Dave, Alberto, and I put in a full day measuring the rock layers and collecting samples from the uppermost part of the sequence. Again, we took care to plot in the positions of a pterosaur skeleton that Pablo had found and the small, armored dinosaur that Ji Shu'an had discovered.

Dave and Alberto took some extra time to examine some layers of gypsum near the top of the sequence. Gypsum forms when lakes and ponds on the floodplain dry up, and the salts in the water precipitate out as gypsum crystals. Consequently, the presence of gypsum indicates that the region underwent periods of increasing aridity late in the history of the rock sequence we were studying.

Meanwhile, Luis and the rest of the crew continued their prospecting across the lake bed, but to make the trek to this area easier, Luis hired a tractor with a trailer to carry the crew to the site (slide 16). Our truck drivers refused to drive off the main dirt road because they did not want to risk getting stuck in the soft lake sediments. The dirt track through the lake was quite rough, especially where small gullies had eroded into the lake bed.

As the tractor swayed and lurched into these ruts, our crew was thrown in the air and whiplashed against the sides of the trailer. Since there was no padding to sit on, the crew suffered several bumps and bruises on their backs and behinds. Although the long hike to the site was avoided, it was debatable whether this remedy was worse than the original malady.

We returned to town about 8:00 and ate a dinner of very spicy, mutton shish kebabs and pita bread outside a restaurant near our hotel. Upon completing dinner, we noticed dozens of townspeople, decked out in their Saturday night finest, migrating toward the school down the street, so we decided to investigate. A huge set of loudspeakers had been set up on the school playground for Urho's weekly dance party. Music ranged from waltzes to rock and roll to hip-hop, and all in attendance chose their own poison to dance to.

As westerners, we stuck out like sore thumbs. Children and young adults immediately asked us to join in, which we did to the best of our ability. Instantly, we were treated as kind of international celebrities, and mobbed by the curious townspeople. We danced for about an hour before seeking our leave to rest up for the next day. It was quite an experience, and we thought that we done our best to be amiable ambassadors. But by the end, we were beat.

August 27 -- Official Troubles We slept in until 10:00 to rest our aching feet and bruised behinds, then took the rest of the morning to write field notes and catch up on other chores. After all, it was Sunday. But in the midst of this lazy recuperation, some unexpected visitors showed up in the form of some local police officials. At first, it seemed that the visit was purely introductory, and they said that they were simply interested in finding out who we were and what we were doing. Luis and Ji Shu'an showed them our collecting permits from the government and our passports, along with describing our activities. This seemed to alleviate any concerns. After about 45 minutes, the officials left, and we ate lunch.

About 2:00 we loaded up for an abbreviated day in the field. The whole crew returned to the area where Nancy was excavating the dinosaur pelvis. While most of the crew prospected, Dave, Alberto and I finished measuring and collecting in the middle part of the rock sequence.

Upon our return to town, the police officials were waiting, which seemed like an ominous sign. After further conversations, they requested that Luis and Ji Shu'an go to Karamay the next day to meet with their superiors, and they also requested that we suspend our activities pending that meeting. Nonetheless, such bureaucratic activities are common in international fieldwork, so we were not terribly concerned.

August 28 -- Packing the Collection In the morning, we photocopied all the crew's passports so Luis and Ji Shu'an could take them to Karamay, and spent the day labeling and packing the fossils and rock samples that we had collected so far, while our two leaders drove off for their meeting. Among ourselves, we joked that perhaps our dancing at the school had been so bad that the local officials took offense.

In the evening, Luis and Ji Shu'an returned with the news that we could resume our fieldwork the next day. In all, things seemed to be back on track, although more meetings with the local officials had been scheduled for the next day.

August 29 -- More Discoveries The clear skies of the morning gave notice that this would be another scorcher, so we loaded up with water and set off for the field, leaving Luis and Ji Shu'an behind to deal with the officials. The rest of us were headed for the site across the lake bed, which continued to produce the greatest abundance of high quality fossils. For David, Alberto, and me, this would be our first opportunity to see that site and ride in the "belly of the beast" behind the tractor.

As we rode out across the brushy lake bed (slide 17), lookouts standing on the back of the tractor yelled out warnings as ominous bumps and ruts approached. But despite sitting on our packs and jackets for padding, we were still thrown about like Ping-Pong balls in a lotto machine. Once having arrived, we set our sights on again measuring the rock layers and collecting samples for magnetic and pollen analysis.

It only took a few hours to complete this project, so we spent the rest of the day prospecting along with the rest of the crew among the picturesque outcrops (slide 18). This was a delightful interlude for us geologists. Pablo found a nice pterosaur skull, and I found some puzzling fossils that appeared to be either plant seeds or insect larvae.

We returned to town about 7:30 to find Luis and Ji Shu'an busily leading the officials from one hotel room to another as they photographed our containers of fossils and compiled a list of the contents. We learned that the fossils were to be impounded, because the officials did not believe that we had all the necessary permits to collect them. It turned out that, although we had permits from the governmental agency that had previously controlled fossil collecting, the responsibility for granting such permits was in the process of changing within the government, and we did not have permits from the new agency.

After the officials had finished their documentation, we gathered at dinner to discuss the situation. It was clear that we were not in any personal danger of being arrested, but Ji Shu'an thought that it would be prudent to conclude our work and return to Beijing, where he and his supervisors could more easily sort out the problems. We all agreed that compliance was preferable to confrontation. So after dinner, we began a hasty exercise to pack and prepare for our departure the next day.

August 30 -- Back to Urumchi We loaded up the vehicles and began the long, day's drive back to Urumchi about 9:00 AM, arriving in the early evening. Despite the fact that the expedition had been cut short, it was nice to be back in a large city and on our way home. After all, it had been a very productive season, assuming that we could gain title to the fossils and samples that we had collected. We had absolutely no guarantee when we set out that we would have much success at all.

In fact, the expedition had been planned as a reconnaissance trip to assess whether the area merited investing in a longer-term project, and the answer was definitively, "yes." So, all in all, we were quite pleased, and Ji Shu'an was quite confident that the fossils and samples would be quickly returned to our custody and shipped to Beijing. With this reassurance in mind, we gathered for our last dinner on the sidewalk of Xinjiang; for, we would fly to Beijing the next evening.

August 31 -- Homeward Bound With the better part of a day to kill before our flight, we decided to go to the provincial natural history museum (slide 19), but we were not in search of fossil displays. Over the course of the last century, numerous remarkable discoveries of mummies had been made in the desert basins of Xinjiang, and several were on display in Urumchi.

The unusual aspect of these mummies was that many of them were exquisitely preserved by the dry climate of the area and some of them, dating back 4,000 years, were clearly remains of caucasoid individuals. For anthropologists, their presence here had been somewhat shocking. What were westerners doing on the outskirts of China that long ago?

Some of the mummies have been highly publicized in books, magazine articles, and television shows, to the point that they have even been christened with nicknames, such as "Cherchen man" and "the Beauty of Loulan." These are place names relating to the sites where they were discovered, and indeed, they are spectacular. The textiles in their clothing is still colorful, and the preservation of their bodies is truly remarkable.

Standing beside them, it was like looking at a recently deceased relative rather than an ancient pioneer from the Middle East or Eastern Europe. It was breath-taking to realize that, three or four thousand years ago, they migrated thousands of miles in order to start a new life in the shadow of such a foreign country.

In the late afternoon, we drove to the airport and flew uneventfully back to Beijing, completing the circle initiated just weeks before. Within a few months, we learned from Ji Shu'an that our fossils and samples had been returned and shipped to Beijing. That set the stage for beginning to plan another expedition, which we hope to undertake in September of 2001, when, undoubtedly, more discoveries and adventures await us in this most remote corner of the world.

The 2000 Expedition to Xinjiang with Dr. Frankie Jackson

Frankie Jackson is a dinosaur egg specialist from Montana State University in Bozeman, where she also teaches Vertebrate Paleontology. She has also participated in several expeditions to Auca Mahuevo and conducted extensive field work at Jack Horner's dinosaur nesting site in Montana called Egg Mountain.

From the plane, the white sand seas of the Gobi stretched to the far horizon with only scattered rocky outcrops breaking the stark landscape in the late afternoon sun. After days of doubt and delay, the expedition was finally becoming reality. Ahead of us lay the vast, largely unexplored reaches of the Junggar Basin, the second largest desert of China. The last major expedition to the region was 37 years ago, when the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology (IVPP) in Beijing explored the region for several field seasons. Dinosaurs from the Junggar, however, remain poorly known, and our work offered an opportunity to fill a few gaps in the fossil record.

Our first day in the field found us south of Urho on a road winding past fields of sunflowers and melons, drab clay brick houses, and corn patches. Men walked the road carrying long scythes and hoes, past low greenhouses of brick and mud, studded with chimney stacks. Yellow squash blossoms trailed over walls that surrounded straight, meticulously tended fruits and vegetables gardens. Agriculture followed the river, but soon gave way to a desolate country of abandoned irrigation ditches and deserted villages. Beyond the ruins of an old salt town on a dry lakebed we found the old IVPP sites and began our own exploration of the area.

For me, the landscape was strangely reminiscent of Montana, only a little more arid. There was little or no wildlife; just raptors riding thermal currents above steep walled narrow ravines. Compared with the fossil-rich outcrops of eastern Montana, the Junggar only reluctantly gives up her dead. Bones are sparse and hard to find. We split up and spread out, searching the dry coolies for scraps of bone. Pterosaur material, a rare find at home, seemed relatively common here - strange that such hollow, fragile bone survived in a flood plain environment. Fossil turtles turned up more frequently than some of us would like - Guillanna preferred dinosaurs but found beautiful skulls with the spinal column still in tact. Day by day, bone by bone, the fossil discoveries increased along with the soaring temperatures: a theropod, short-snouted crocodile, a pterosaur wing, an anklylosaur. The paleo-environment began to take shape, and the picture started to come into a little better focus.

The expedition also offered a rare opportunity to see rural China and to compare the cultural and economic realities with that of rural Montana. Stark differences lie in the amenities that we take for granted - plumbing, cars, electricity, medical care, and education. But similarities also exist: an agriculture-based economy, a slower pace, and a greater sense of “community”. No where was the latter more apparent than street dances where little children, parents, grandparents, and teenagers all joined in dancing as the music shifted from ballroom to hard rock as the strobe lights flashed cadence against the darkness. We sat at a table one night talking with two students, the only English we had heard spoken in weeks. Soon they were translating for their father who joined us, then his wife, their grandmother and others. The father encouraged his son and daughter to go to the house and eat dinner but they preferred to stay and talk. He smiled and soon came back with food to share with all of us. The scene had a Montana familiarity and I was impressed more by the similarities I found in people than in their differences. Working in western China offered a unique chance to experience a side of Chinese culture seldom seen by traditional tourist travel, and I look forward to future expeditions.